David Mosse begins his book The Saint in the Banyan Tree: Christianity and Caste Society in India (UC Press, 2012) with the story of a miracle-working tree in the rural village of Alapuram (a pseudonym) in Tamil Nadu, southern India. As long ago as the late 1600s, the story goes, four brothers brought a tree cutting to the village from a coastal shrine. It was a banyan tree: the tree known for its complex, tangled growth and roots-turned-branches. In the tree was St James (Santiyakappar). The brothers' descendants are said to have settled in the village and become the subordinated Pallar caste -- among the so-called "untouchables." Already in the 1730s, Jesuit missionaries in the area wrote home about the crowds of people that traveled to the tree shrine to ask the saint for favors and to fulfill vows. Some centuries later, in the 1980s, David Mosse first visited the village to conduct anthropological fieldwork, and observed how people from different castes in the village participated in what had become the elaborate, Catholic Santiyakappar festival. And that is how the story of The Saint in the Banyan Tree begins. Then it grows into a complex, rich story about a village and about India, about a saint and about Christianity, about dalits ("untouchables") and caste society, about Jesuit letters and history, fieldwork bike trips and anthropology.

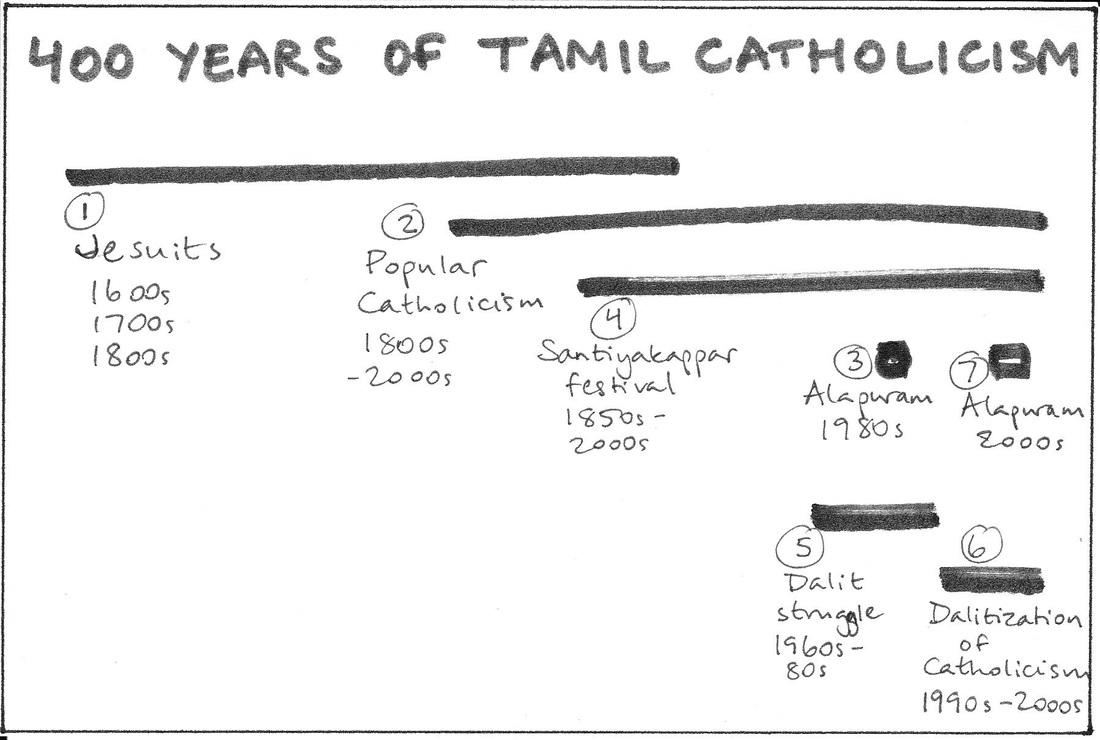

The book has seven chapters (along with an introduction and conclusion), most of them drawing on some combination of historical and ethnographic work. I first thought of these different chapters as "windows" onto 400 years of Tamil Catholicism, but it is perhaps more true to Mosse's account to think of them as "building blocks" or something similar: these are the blocks we have to work with, in this study, to build an understanding of how people built (or practiced) Catholicism over this time period, in this place.

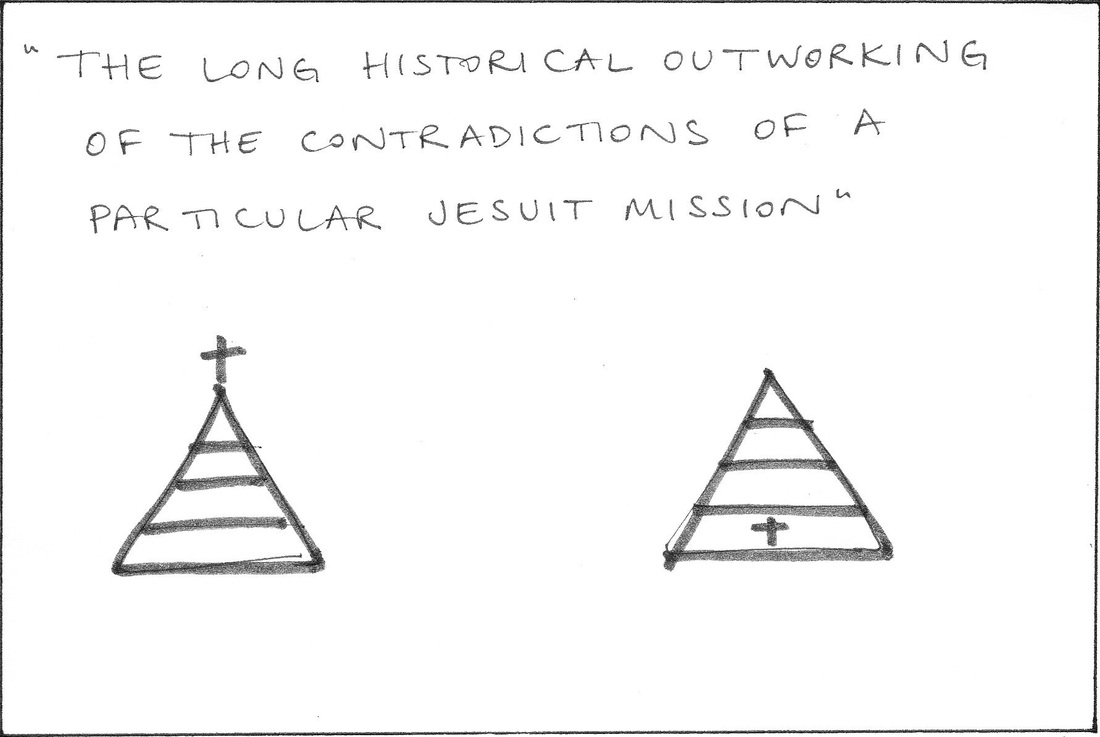

The central question that Mosse explores is a long historical paradox -- or a long "outworking" of contradictions (p.24): How has Christianity, over the centuries in Tamil Nadu, worked to bolster and directly reproduce caste society while also introducing forms of thought and action that have undermined, even struggled directly against, caste society?

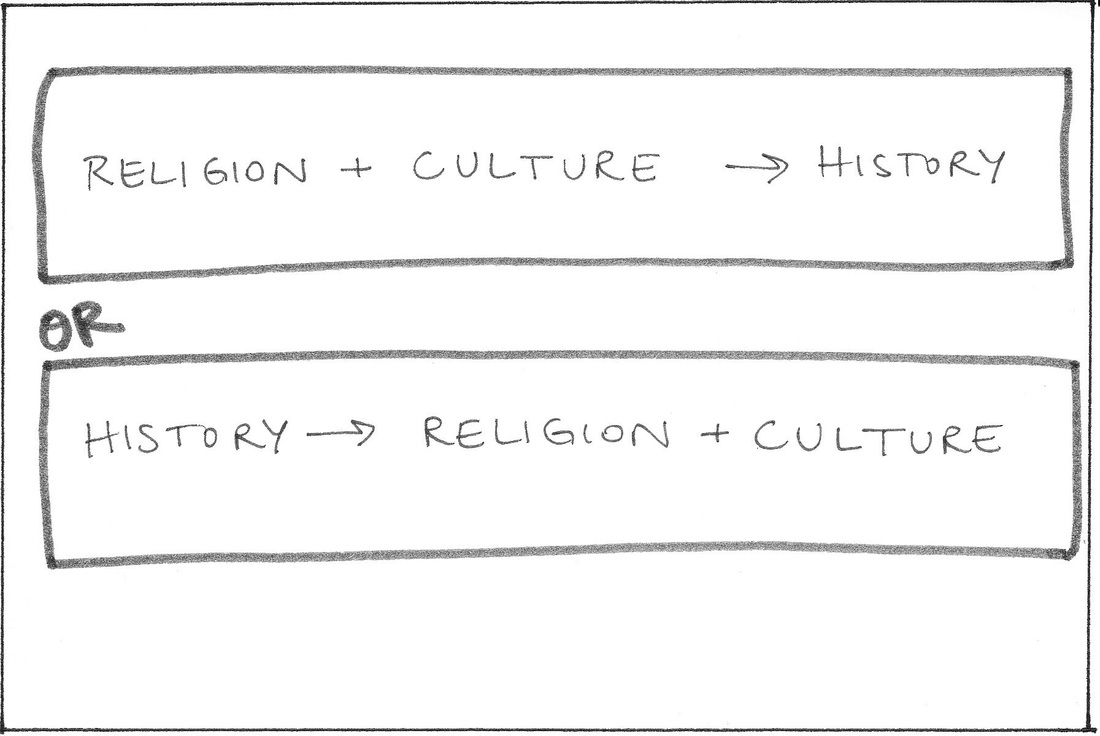

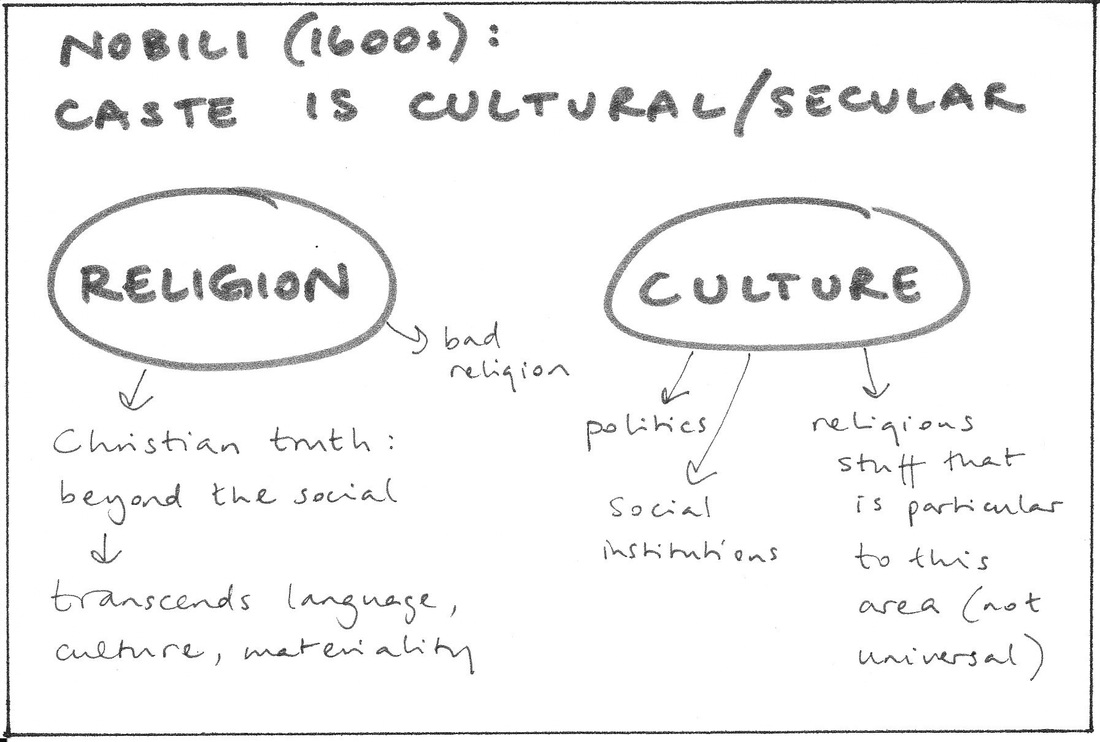

I think the banyan tree and its roots-turned-branches is a fitting image for a broader theme here: While it is easy to think of Christianity as the historical starting point when considering the history of Christian mission, it is more accurate, as Mosse argues, to think of Christianity as a historical outcome. Throughout the book Mosse (drawing on Keane) demonstrates how the domains of "religion" and "culture"/"secular" were produced (i.e. how different groups attempted to purify and separate them) over the centuries in Alapuram and surrounding areas: "Jesuit missionary religion produced the 'secular' - the realm of caste, politics, and culture - even before the colonial secular produced the modern category of 'religion'" (p.xi-xii).

Starting with one of the early Jesuits in India, Nobili, Mosse shows how the Jesuits wrought the category of secular/political "culture," categorized caste as "cultural," and worked hard to continuously situate themselves as separate from "culture" (in the domain of "religion"). In order to do this it was important to establish the premise that Christian truth transcended culture: it was "beyond the social" (p.xii). Interestingly, this is today regarded as more of a modern Protestant achievement, but, as Mosse argues, it was in this case a historical Catholic move that cannot be seen simply as anticipating modernity or Protestantism.

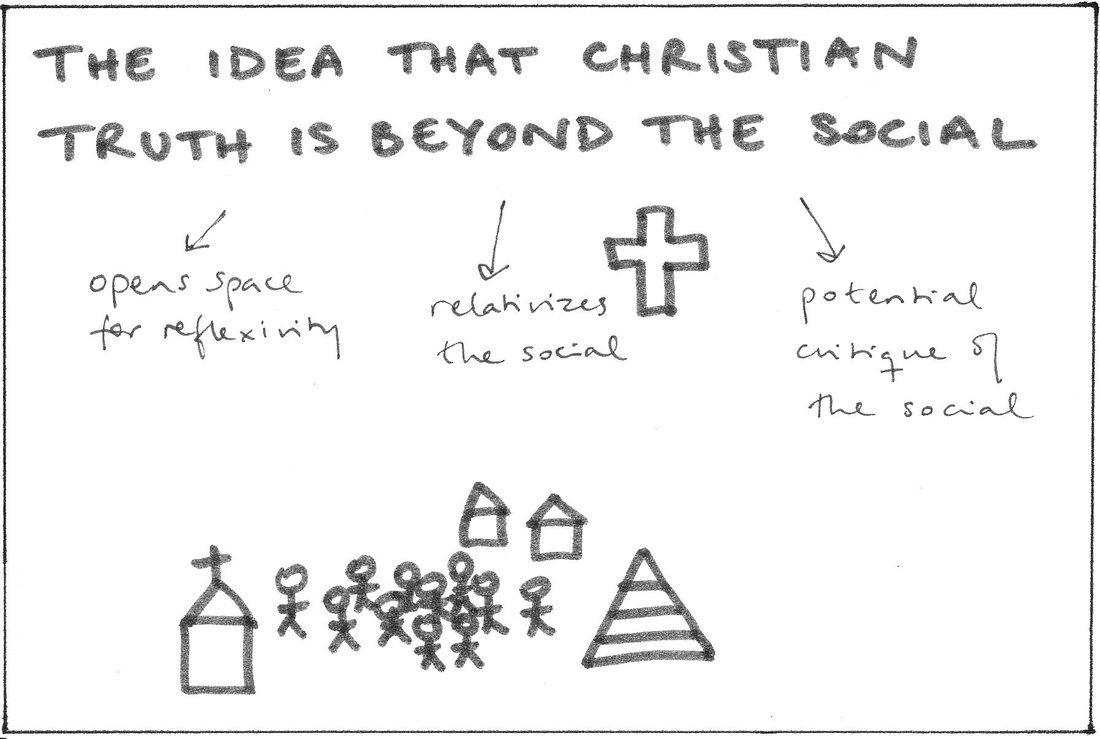

The idea that Christian truth is beyond the social is, Mosse suggests, a significant factor in understanding the paradoxical and complicated interaction of Christianity and caste society. This idea first allowed caste to be accommodated by the Catholic church. There were even walls within churches to separate people of different castes. But at the same time, the idea that Christianity somehow relativized the social also opened up a space for reflexivity, and, in due course, potential critique of the social order (though in Tamil Nadu it took three and a half centuries before this fully manifested).

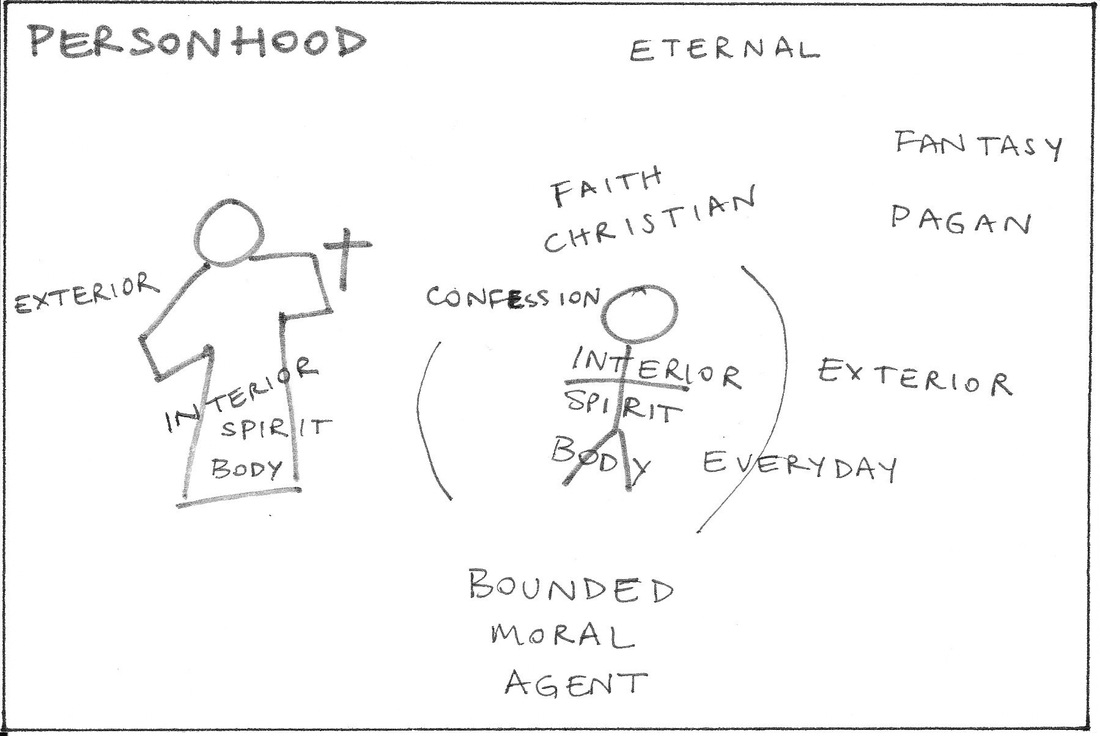

Christian truth needed to find expression in everyday life. Mosse writes that "French Jesuit priests worked hard on their Tamil parishioners to get them to separate the Christian from the pagan, the eternal from the everyday, the interior from the exterior, faith from fantasy, spirit from body" (p.64). Of course, in practice things were not so purified.

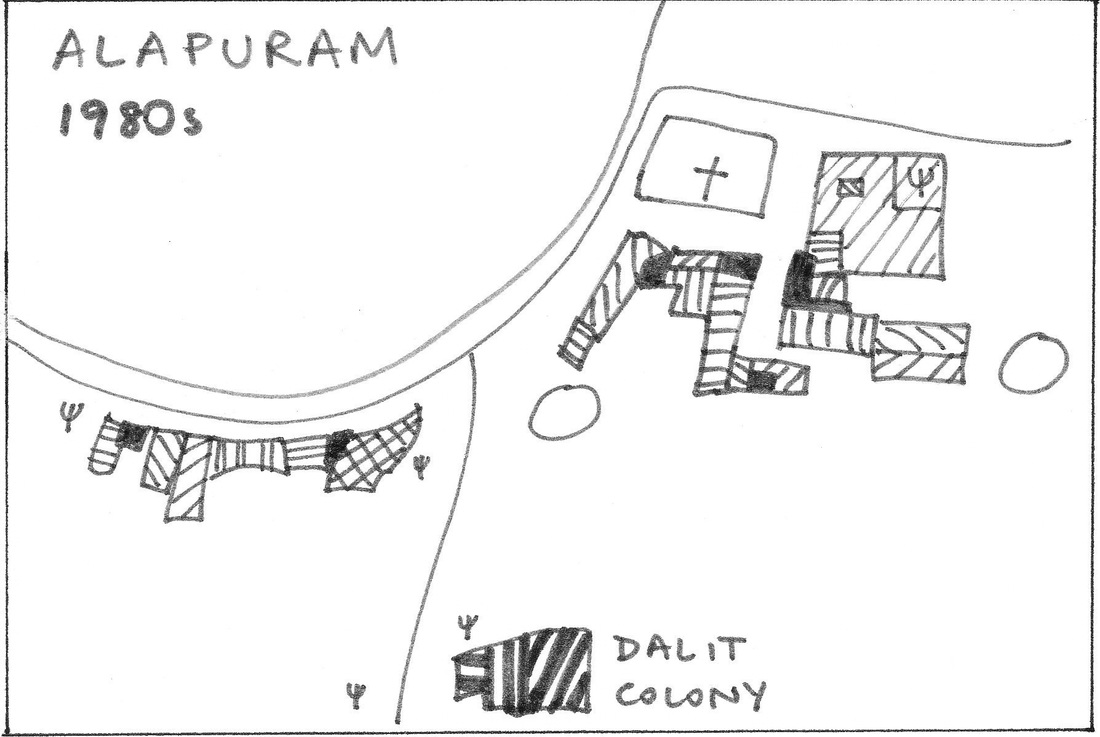

All of the Jesuit mission engagements happened within a society that composed and performed caste (p.96). One of the most striking images in the book, to me, is Mosse's map of Alapuram village during his first round of fieldwork in the 1980s (p.103): every street or section is marked as being occupied by one of thirteen castes, hinting at the later descriptions of careful social differentiation (and discrimination) in the midst of everyday village life.

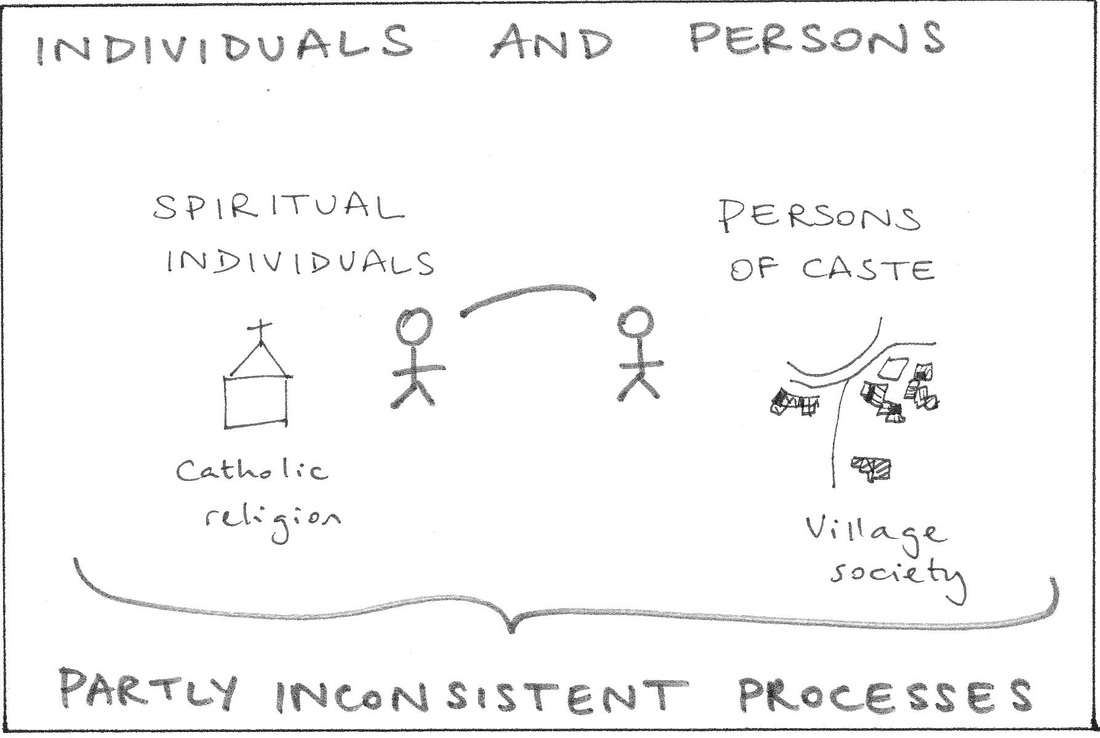

The book is framed as a project that focuses on the social and institutional. This focus allows Mosse to describe the institutional contradictions that arise as villagers try to participate simultaneously in the Catholic religious realm and caste-based village society, and how the institutional friction leads to changes over time, e.g. in the way the Santiyakappar festival is celebrated.

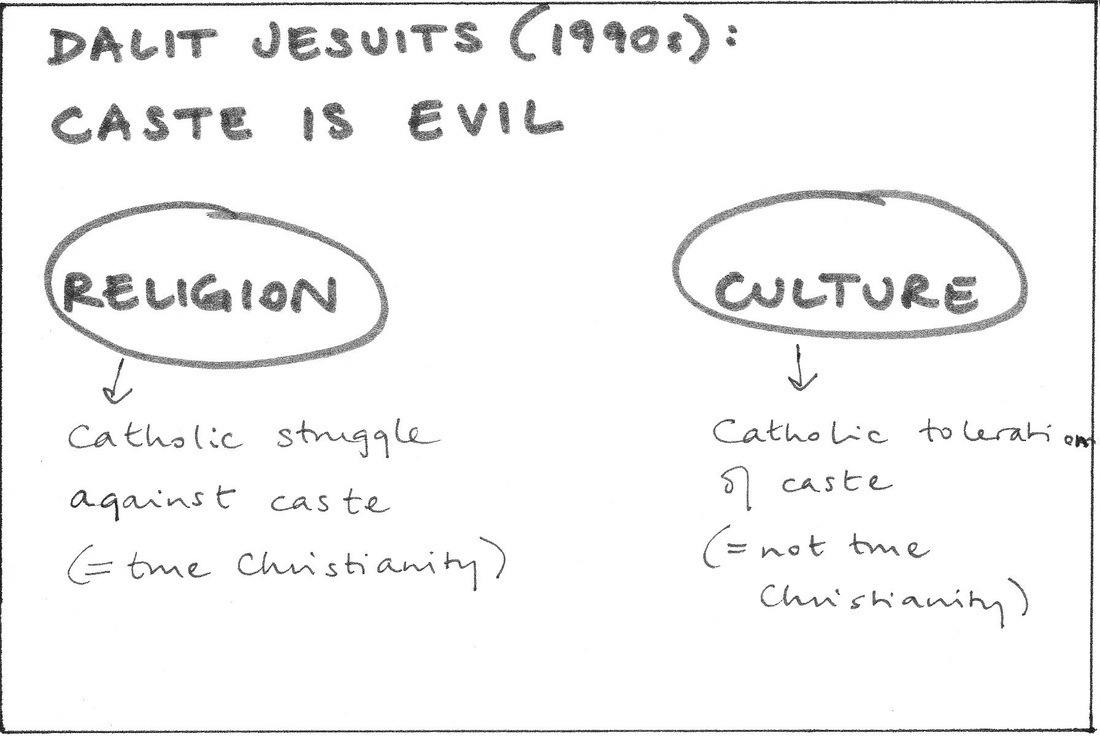

During the second half of the twentieth century some of the conceptual contradictions of Tamil Catholicism were worked out further in a new historical twist: dalit Christians began to "dalitize" Christianity, in a type of reversal of the way in which the early Jesuits had "Brahmanized" their message. Several of the caste divisions have gradually been removed from the Catholic Mass, the Eucharist, festivals, cemeteries, and church buildings. But Mosse's interviews with dalit priests and nuns, who speak of the continuing struggle to be seen as fully human within their own church, present some of the more raw material in the book.

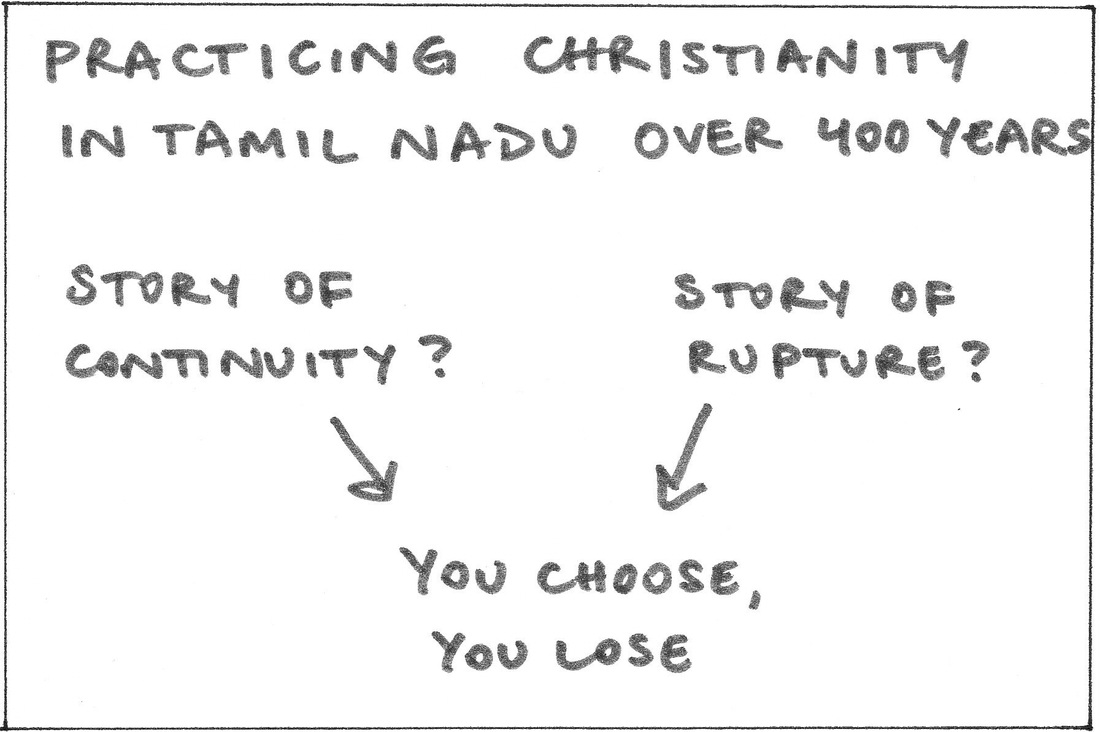

So that is perhaps a flippant way of phrasing it, but I think it captures some of Mosse's conclusion, namely that both continuity and rupture can be traced over time in the local, historical, social forms of Christianity in Tamil Nadu. Building on the premise that Christian truth was beyond the social allowed Catholicism to be "profoundly localized into existing social and representational structures" (such as caste), while at the very same time becoming "a source of distinctive forms of thought, action, and modes of signification that are potentially transformative" (p.28). More broadly, this is the book's welcome contribution to the discussion in the anthropology of Christianity over whether studies of Christianity should focus on continuity or discontinuity: over the long term you cannot avoid studying both.

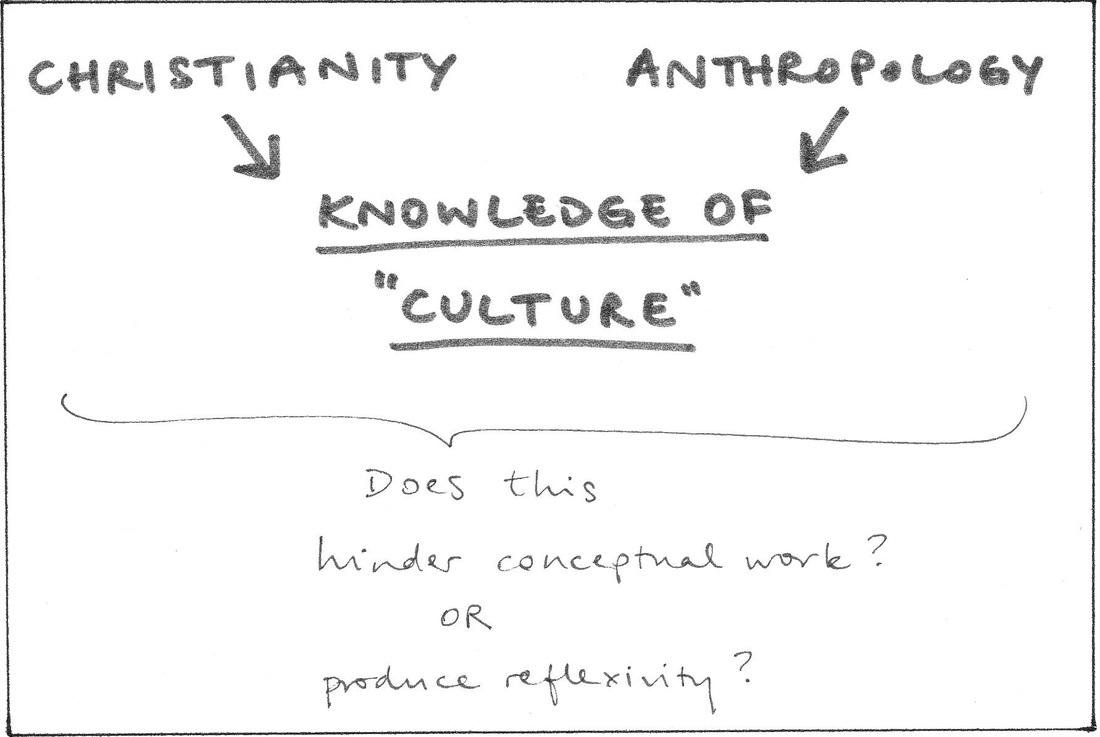

In my opinion Mosse also makes a contribution to another question in the anthropology of Christianity, namely: how hindered are we by the "Christianity of anthropology"? He paints a picture of the ways in which the Catholics in southern India depicted culture, relativized it, and claimed knowledge of it from the universalizing perspective of Christian truth -- and then points out the similarity of this project to the anthropological project, which is one of depicting culture, relativizing it, and claiming knowledge of it from the universalizing perspective of anthropological theory. But instead of concluding that this type of conceptual similarity between Christianity and anthropology is limiting (as Asad and others have done), Mosse draws on an alternative lineage to suggest that perhaps Christianity and anthropology can both employ the sociological perception that enables one to think about social form -- and critique it.

This final index card is also a little simplified, but I wanted to note down one of the thoughts that has stayed with me since reading The Saint in the Banyan Tree: Mosse is not so much interested in explaining what "Christian culture" is, as he is in exploring what Christianity does -- in specific time periods and places (and here he does agree with Asad that religion is constituted primarily in a realm of practice, producing experiences and knowledges). And his book is indeed an unusual, insightful exploration of the contradictory things that Christianity has done, and of how Christianity has been done, in one time and place -- with implications for many others. In sum: we should all study banyan trees more closely.